Let me start things off with a disclaimer - I am not an economist. I don't even

pretend to be an economist; I'm a nuclear engineer by training (I hold Ph.D. in Nuclear Engineering). That notwithstanding, economics (and specifically, the economics of energy) are a side interest of mine. So it was with mixed interest and trepidation when I read a recent piece by libertarian economist Veronique de Rugy from the upcoming July issue of

Reason, entitled "

No to Nukes."

Plausibly, de Rugy's animating complaint (given Reason's market-oriented focus) is in the subsidies for new nuclear (specifically, when I followed up with

de Rugy on Twitter,

she pointed out the issue of

loan guarantees, although nowhere does this specifically appear in her piece). The piece itself is nothing new, however - the bulk of it is in fact

a retread of a suspiciously-timed nuclear hit piece which appeared literally two weeks after the Fukushima disaster. (One gets the distinct impression that, despite her protestations to the contrary, de Rugy is more than happy to dance on what she perceives to be nuclear's grave, particularly given her timing and choice of targets.) In reality, the piece seems to follow on to a frustrating trend of pro-fossil contrarianism as of late,

particularly in libertarian circles (contrarian in the sense of singling out the most economical, carbon-free competitor to fossil fuels for special scorn on economic grounds); although perhaps this contrarian turn owes to the fact that conservative heavyweight think tank

Heritage has cornered the market in

advocating nuclear energy as a free-market energy source. (Who said hipsterism is limited to fashion and terrible beer?)

de Rugy's piece begins with an overly long introduction detailing to the reader why nuclear power was destined to fail to live up to its promises, including citing public opinion which she describes as having " remained steadfast against the technology ever since [Three Mile Island]" (although someone may want to refer de Rugy to the latest

polling data on the

subject), along with other issues, such as "[d]isputes over waste disposal [which] have never been resolved" (once again however,

these are political rather than technical matters).

Finally we get to the meat of the matter - it would appear that a restart of the nuclear industry is, "[...]not just bad politics. It’s awful economics." Well.

To this end, de Rugy characterizes the recent decision by the NRC to grant Southern Nuclear company a license to build two new AP1000 units at the Vogtle site - the first new units in 30 years, as "[...]

an act of desperation by a president who has realized he is running out of other options." Fortunately, contrary to the opinions of a economists with a particular axe to grind, the decision to award Southern Company is not in fact in the hands of the president, nor are operating licenses granted upon individual opinions about economic viability of the project - they are voted on by the commissioners of the NRC on the basis of safety alone. This fundamental misunderstanding of the process is pervasive throughout the rest of the piece.

Much of the piece is particularly scarce on actual sources and utterly devoid of hyperlinks (however, given the fact that the piece is a re-tread of her prior post-Fukushima piece, most of her sources appear to be taken from there). de Rugy cites a 2009 MIT study by Ernest J. Moniz and Mujid S. Kazim as evidence of nuclear's uncompetitive costs; one assumes she is referring to MIT's "Future of Nuclear Power" project which includes cost projects of nuclear compared to other conventional fossil sources under a variety of circumstances. In the 2009 update, it reports the following cost comparison: assuming current cost of capital, coal clocks in at 8.4 ¢/kWh, natural gas at 6.5 ¢/kWh, and nuclear at 8.4 $/kWh. The authors specifically note however that this includes a current "risk premium" to capital costs for nuclear - recalculating capital costs at comparative market rates (absent the "risk premium"), they come up with a number far closer to gas and coal: 6.6 ¢/kWh. Even assuming the risk premium stays, with a carbon capture and storage the cost for coal and gas quickly reaches near-parity with nuclear once more. Such an analysis is also borne out in applying levelized cost of electricity estimates to EIA data, resulting in similar conclusions.

Much of the piece is particularly scarce on actual sources and utterly devoid of hyperlinks (however, given the fact that the piece is a re-tread of her prior post-Fukushima piece, most of her sources appear to be taken from there). de Rugy cites a 2009 MIT study by Ernest J. Moniz and Mujid S. Kazim as evidence of nuclear's uncompetitive costs; one assumes she is referring to MIT's "Future of Nuclear Power" project which includes cost projects of nuclear compared to other conventional fossil sources under a variety of circumstances. In the 2009 update, it reports the following cost comparison: assuming current cost of capital, coal clocks in at 8.4 ¢/kWh, natural gas at 6.5 ¢/kWh, and nuclear at 8.4 $/kWh. The authors specifically note however that this includes a current "risk premium" to capital costs for nuclear - recalculating capital costs at comparative market rates (absent the "risk premium"), they come up with a number far closer to gas and coal: 6.6 ¢/kWh. Even assuming the risk premium stays, with a carbon capture and storage the cost for coal and gas quickly reaches near-parity with nuclear once more. Such an analysis is also borne out in applying levelized cost of electricity estimates to EIA data, resulting in similar conclusions.

Taking up the example of the French (with their nuclear-heavy energy portfolio), de Rugy asserts that because of the France's (state-subsidized) industry, French consumers pay more for electricity. Specifically, she writes:

But producing nuclear energy in France is not magically cheaper than elsewhere. French citizens are forced to pay inflated costs to support grand government schemes, such as the decision made 30 years ago to go nuclear at any cost after the first oil shock in 1974.

Really?

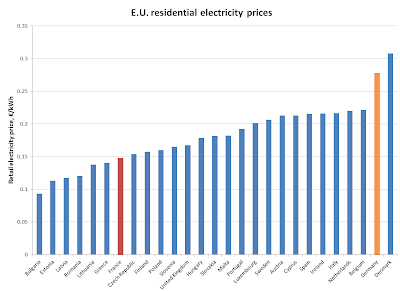

Going to the data, the opposite is in fact true: France has one of the

lowest retail electricity prices (the 7th lowest in the E.U.); compare this to Germany, which has recently phased out nuclear entirely, which pays the second-

highest rate. (Again, these are not hard things to find, but something de Rugy asserts with no evidence and in clear contradiction of the data.) She might try to argue that consumers pay indirectly, but nowhere has evidence been presented to support this, nor is it supported by retail electricity price data.

de Rugy's main thrust here of course is that capital costs for nuclear in the U.S. are little different than those than in nuclear-friendly France, relying on the analysis of the

Vermont Law School's Mark Cooper, an individual who isn't exactly private about his own agenda when it comes to nuclear. (Hint:

he's not a fan.)

Again, one gets the impression the data is being cherry-picked to fit the desired conclusion. de Rugy makes an incomplete comparison here, citing the high "overnight cost" estimates for nuclear capital costs compared to coal and natural gas, while neglecting to inform her readers that this alone is a highly misleading comparison. (To see how this process is properly unpacked, even with natural gas still coming out favorably compared to nuclear, I invite you to see how Dr. James Conca unfolds the data).

To wit: "overnight" cost is a rough estimate of total capital cost (i.e., total money which must be invested to build the plant), assuming the plant "overnight" - i.e., without the borrowing costs (in other words, interest on loans which continues to pile up while plants are being built and not generating revenue), something which particularly dominates nuclear costs. However, a more accurate comparison is the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE)- something which calculates both the capital cost

and operations & maintenance costs (which include fuel - a cost which dominates natural gas economics). The LCOE calculates the "break-even" cost of electricity from a plant given the projected costs over the plant's lifetime, with a reasonable discount rate (for example, the expected return of ~3% on treasury bonds) over the life of the facility. Given that the expected lifetimes of different facilities can vary widely by type (i.e., the current fleet of nuclear plants will almost all be relicensed to operate for a total of 60 years, with some potentially operating up to 80 with facility improvements and upgrades), this makes for a more useful comparison of the

actual cost of electricity. Once again, something absent from de Rugy's analysis.

Indeed, taking this out to the logical extension - if nuclear plants were wholly unprofitable to build and operate, why in the world then would operators of the existing fleet of 104 reactors not simply turn each one off tomorrow, much less put a dime into maintenance outages which run up into the millions of dollars? The answer of course is because this is

not true; nuclear plants are indeed expensive to build (due to capital costs, including the borrowing costs associated with construction times), but the

marginal cost of power from a nuclear unit is tiny - namely because most of the cost is in the cost of capital itself. Nuclear in this sense represents the

opposite economics of natural gas, which has a low front-end cost but whose costs are generally dominated by fuel price. (Thus, the levelized cost - something de Rugy does not look at - is extremely dependent upon assumptions of future fuel prices - hence why nuclear is often seen as a hedge against future fossil fuel price increases.)

However, de Rugy comes back with the follow-up that such estimates of nuclear cost come "after taking into account a baked-in taxpayer subsidy that artificially lowers nuclear plants’ operating costs." Looking at the

broader picture of historical energy subsidies however, this point doesn't seem to carry the impact de Rugy seems to think it does - from the period of 1950-2010, nuclear has been the recipient of about 9% of total federal energy subsidies, compared to a shocking 44% for oil. (For those following at home, the rest include: Natural gas - 14%, Coal - 12%, Hydro - 11%, Renewables - 9%, Geothermal - 1%). Most of nuclear's subsidy has,

contra de Rugy, not been focused on the regulatory side (although the study does point to an approximate regulatory subsidy of $16 billion over the total time period) but R&D, which should surprise few who are conversant with the history of nuclear. (Oil, by contrast, receives the whopping share of its calculated subsidies from tax policy and regulation, while natural gas has almost exclusively benefited from tax policy).

Notably absent from de Rugy's analysis is how the most important subsidy fossil fuels (especially coal) have come to rely upon, which is treating the atmosphere like an open cesspool. Indeed, looking to the above costs from the MIT study, were we truly dealing with a "level playing field" in the sense that carbon-intensive industries were required to give their waste products the same degree of scrutiny that nuclear already does, the much-ballyhooed "cost difference" largely vanishes. (Again however, discussions of energy subsidies invariably seem to only go one way: like a claymore.)

No doubt though de Rugy is invoking the issue of nuclear liability insurance of course (known under the moniker of the "Price-Anderson Act", passed in 1957). What is not noted is the exact taxpayer liability to date under Price-Anderson - which is exactly $0. Again, contrary to the claims of nuclear opponents like de Rugy who dress up their objections in economist's language, nuclear is not "uninsurable" on the private market - in fact, each nuclear unit is required to carry an individual liability of $375 million; following the exhaustion of the individual commercial policy, each operator-licensee is required to kick in up to another $111.9 million (pro-rated), producing what amounts to a collective cross-insurance arrangement of $11.975 billion. One can dispute whether such a sum is "sufficient," but the idea that the industry is utterly absolved of tort liability is clearly at odds with the the current reality.

When I pressed de Rugy over what particular subsidies she was complaining about and why her complaint so specifically singled out nuclear (looking at her publication history, there is

nary an article devoted to the issue of energy subsidies for other sectors), she responded by pointing me to

an analysis she did on the market-distorting effects of loan guarantees. (This

after I pointed out that I was in favor of removing

all subsidies - but it would seem, like many in the punditry business,

the conclusion comes first).

Frankly, I won't get into all of the analysis - because once again, I am not out to defend loan guarantees or any other form of energy subsidy. However, one thing that did jump out at me once more was the use of extremely cherry-picked data in her report - the few items that do mention nuclear (most of the piece pertained to loan guarantees for solar - which incidentally, was

not required to pay the credit subsidy fee which nuclear was) are, shall we say, "factually challenged." de Rugy rolls out the

several-times-over debunked trope of the 50 percent default rate with nuclear loan guarantees - based on poorly-documented projections over a program which was never passed. While de Rugy immediately pointing out that the CBO revised this number (without specifying how much), the supporting evidence she gives to this revision

doesn't even pertain to civilian nuclear power - rather, the study she points to is a comparative

economic analysis of nuclear power for

naval propulsion.

The only other nuclear-specific studies de Rugy cites in this study come from Peter Bradford - a well-known anti-nuclear activist with the

Nonproliferation Policy Education Center (simply

google "Bradford" and "nuclear" if you don't believe me) - along with Henry Sokolski (also affiliated with the same). The extremely selective use of sources known to have a hostile agenda to nuclear (that is, when the sources even

accurately refer to de Rugy's claims) again strongly implies a rushed, cherry-picking approach that implies a "conclusion-first, evidence later" approach that is all too familiar with established punditry. Indeed, it might make for impressive-looking studies (and good sound bites), but it hardly suffices for serious scholarly work. Indeed, if the evidence is as strong as she claims it to be, it would behoove her case greatly to find such evidence from more objective and less clearly agenda-driven sources.

Of course, all of this is the problem: even rather sloppy studies like this, particularly when attached to someone with a Ph.D. in economics, sound plausible and require the time and energy to deconstructing their myriad of errors and misplaced assumptions - something which amounts to a non-trivial task for one when most of their day is typically occupied by honest employment, alas.

Few environmentalists are willing to take such a self-marginalizing position (although clearly that number is far from zero, if the ongoing campaigns against Vermont Yankee and Indian Point are any indication). Those that do inevitably fall into two categories - those that (disingenuously) assert that the gap can be filled nearly immediately with renewable sources (despite the mathematical difficulties of such a claim), falling back onto the idea of natural gas as a "bridge fuel" (again failing the basic arithmetic rule that half the carbon dioxide emission of coal, easily the dirtiest source available, is still far greater than zero, or close enough when all emissions are factored in over the entire lifecycle), or when pressed, falling back upon the idea of "energy austerity" - asserting (again, under highly questionable premises) that the energy deficit can simply be closed by using less - either by efficiency or simply by imposed austerity.

Few environmentalists are willing to take such a self-marginalizing position (although clearly that number is far from zero, if the ongoing campaigns against Vermont Yankee and Indian Point are any indication). Those that do inevitably fall into two categories - those that (disingenuously) assert that the gap can be filled nearly immediately with renewable sources (despite the mathematical difficulties of such a claim), falling back onto the idea of natural gas as a "bridge fuel" (again failing the basic arithmetic rule that half the carbon dioxide emission of coal, easily the dirtiest source available, is still far greater than zero, or close enough when all emissions are factored in over the entire lifecycle), or when pressed, falling back upon the idea of "energy austerity" - asserting (again, under highly questionable premises) that the energy deficit can simply be closed by using less - either by efficiency or simply by imposed austerity.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)