Being generous to the poll, one can suppose some confusion arises over the fact that natural gas has been largely responsible for electricity capacity additions within the last decade in the U.S. Still then, one wonders why nuclear energy is excluded from the choice provided.

|

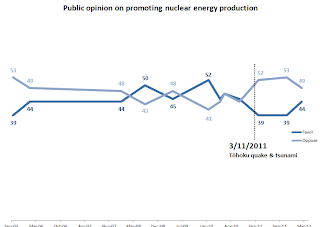

| Public support of expanded nuclear energy production (adapted from Pew) |

Digging deeper into the survey, nuclear does show up; what it reveals further highlights the dichotomy illustrated above. Despite rising energy prices overall (both at the pump and in the retail electricity sector), public support clearly shows a disconnect when it comes to fossil fuel exploration versus electricity production. In general, nuclear energy is still recovering in terms of public opinion one year later following the Great Tōhoku Earthquake and tsunami and resulting nuclear crisis at Fukushima.

|

| Public support for off-shore oil drilling, from Pew |

What is perhaps revealing is to contrast this to the trend in public opinion on offshore oil drilling following the Deepwater Horizon blowout and massive spill in the Gulf of Mexico - something much closer to home. Unlike nuclear energy, public opinion has generally settled back into its prior setting (enjoying broad majority support) within less than two years, with large majorities favoring expanded offshore oil drilling. While favorable opinion on nuclear expansion appears to recovering, it is still unlikely to achieve the broad support that offshore oil exploration has - again, despite the very visible risks of the latter.

Perhaps also noteworthy is the relative "stickiness" of public opinion - one observes that following a high-profile event (e.g., Deep Water Horizon or Fukushima), public opinion eventually gravitates back to its historical average, implying relatively firmly entrenched opinion with a handful of the public being swayed by major events.

|

| Public support for increased federal funding for alternative energy research, from Pew |

For comparison, Pew also evaluated public opinion of increased financing for alternative energy sources, including solar, wind, and hydrogen. Interestingly, public support for such increased financing has been on a slow decline; thus, in spite of the lede in the New York Times blog that this is somehow a newly emerging phenomenon compared to conventional sources, it is a process which appears to have been dragging on for some time. Indeed, the trend appears to have begun well before high-profile events such as the Solyndra bankruptcy and resulting scandal; while public support slowly continues to drop afterwards, the decline began well before this and continues steadily afterwards. It is difficult to speculate what one may take away from this other than the fact that if the Republican nomination fight is any sign, Americans are notoriously fickle, constantly in search of an appealing hypothetical alternative which simply does not exist.

|

| Weekly average retail gasoline prices (all grades), via EIA |

Why the quicker"snap back" in public opinion (or faster-acting amnesia, if you prefer) for oil and gas exploration, in particular? A likely culprit is the higher visibility of rising fuel prices (directly connected with the price of oil); particularly strong is the correlation between public support for oil and gas exploration and the price at the pump.

|

| Average retail electricity prices, from EIA |

Retail prices for electricity have also been on the rise, but such a rise has been much more of a slow creep; with the average rising slowly over a matter of months rather than weeks. Plausibly, electricity consumption is perhaps seen as something consumers can exert some degree of influence over, be it through conservation or efficiency improvements, while demand for gasoline is relatively fixed (at least with respect to workplace commuting).

| % in favor | |||

| Rep | Dem | Ind | |

| Allowing more oil & gas drilling in U.S. waters | 89 | 50 | 64 |

| Giving tax cuts for oil & gas exploration | 61 | 38 | 42 |

| Promoting the increased use of nuclear power | 54 | 37 | 45 |

| Requiring better fuel efficiency for vehicles | 67 | 88 | 77 |

| Spending more on mass transit | 52 | 74 | 67 |

| More federal funding for alt. energy research | 52 | 81 | 70 |

What the above data puts to lie is the myth that members of either major political party are interested in an "all-of-the-above" energy strategy, something frequently invoked as a toll to political correctness (by countless nuclear advocates included) but not reflecting anyone's actual opinions. Indeed, among self-identified Republicans, while a much larger number favor nuclear energy expansion compared to Democrats, it is still a far less popular option than most scenarios involving either the development of additional fossil fuel resources or extension of existing supplies (i.e., fuel efficiency mandates). With respect to Democrats, overwhelming majorities seem to place their faith in measures such as conservation (including vehicle efficiency) and alternative energy research, particularly compared to the use of nuclear energy (again, issues of numeracy be damned). Only self-described independents might be considered to favor an "all of the above" strategy, although their support of such is divided at best.

In other words, despite the popularity of declaring favor for an "all-of-the-above" energy strategy, such a mantra is typically invoked simply as a cover-all in order to push forward an individual's energy priorities without having to engage in inconvenient discussions like practicality, cost, or environmental impacts. And again - this is something which occurs across the board - a token statement given which if the above is any indication, few actually believe (at least with any fervor).

What is perhaps most evident from the above is sharp evidence for the hypothesis that in the political conversation over energy, Americans are talking past one another. Again - given the fact that very little oil is burned directly to produce electricity, most of the conversation on fossil fuels comes down to energy for transportation, with natural gas coming along for the ride in the sense that it may conceivably occupy both sectors. Meanwhile, absent dramatic advances in battery technology, renewables show nearly zero intersection with the transportation sector.

Meanwhile, the lesson in this for advocates of nuclear, both looking at the historic trend in public opinion of oil drilling compared to nuclear energy as well as divisions among party lines is that in order for nuclear to command strong majorities of public support, the issue of ever-rising electricity prices (rising in tandem with global demand for overall energy resources, including coal and natural gas) must be continuously hammered, along with nuclear energy's role in providing affordable, base load electricity. The issue of electricity prices can and does motivate groups - and indeed, sometimes in the wrong way. An example would be the AARP's opposition to Iowa's recent legislative action toward allowing construction-in-progress financing of small modular reactors. The reason? Concerns over electricity prices for those living on fixed incomes. Again, despite the fact that the conclusion is logically perverse in this case, the connection is quite clear.

So what does all of this come down to? Ultimately, it reinforces the issue of fungibility in energy. For nuclear to enjoy the same resilience as fossil fuel sources with public opinion, it must also share the same perception of indispensability. Right now, nuclear is viewed as a fungible energy source - again, one can refer back to the way in which both Republicans and Democrats appear to be making a mental substitution (natural gas or renewables, respectively), thus making nuclear expansion appear to be an "optional" energy strategy for a resource (and carbon)-constrained energy future. Until advocates drive home the essential nature of nuclear energy production with respect to both future energy prices and the environment (i.e., demonstrating that nuclear energy is not so easily substituted without unacceptable economic and environmental trade-offs), it is likely support for nuclear will languish at its historic value near 50%, with sharp and persistent divisions among partisan lines.

Steve,

ReplyDeleteSelf-identified republicans are above 50% on all counts while independents are at 45% on nuclear. How does that lead to the conclusion that only independents might be considered to favor an all of the above strategy?

@Fritz - my first-glance interpretation pertains more to the general strength of support across a broad number of categories. The "consensus" of Republicans (close to 90%) seems to be oriented toward fossil fuel exploration - you're correct that at the very least, nuclear has a majority among self-identified Republicans, but honestly - again, solely my interpretation here - is that it's pretty weak, given that even vehicle efficiency mandates carry more support. Basically, the bulk of "strong" Republican consensus is almost entirely weighted toward oil & gas - this doesn't mean nuclear doesn't have support, but it certainly doesn't command the kind of consensus that fossil sources have.

DeleteGoing back to independents, my thought was not so much with respect to nuclear as it was the stronger consensus among a broader swath of energy options.

Overall, it doesn't seem like *any* group enthusiastically embraces the "all of the above" strategy, although I suppose if you look at it on the basis of majorities, rather than consensus, one can make the argument that this is more favored by the Republicans than any other group. Basically though, my main thought here was the disparity between rhetoric and actual demonstrated support - for folks in both parties who call for an "all of the above" strategy, support seems rather fractured at best. "All of the above" seems more like code words for, "As long as I get what I want."

Your mileage may vary, of course.

Without expressing a personal opinion, I do want to point out that the "all of the above" attitude toward energy is central to President Obama's reelection campaign.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0eQs2EBWU3M

Good post by the way.

On the subject of fungibility though, you mention that renewable electricity sources like wind are not fungible. There is something missing here, which is that petroleum products ARE fungible to a very major extent. An oil distillation tower produces an entire range of products mostly distinguished by their Carbon chain length. These products are all destined for a wide range of different uses, but there are several reasons there's more to the story than that. There is product on the margin that can be directed to more than one use. The sophistication of the stratification of hydrocarbon products can't be understated, it's created virtually an entire commodities trading industry to itself. One type of product can also be converted into another. Particularly, long Carbon chains can be broken into smaller molecules via "hydrocracking" and other technologies. This more advanced type of manipulation comes at a cost, but it was developed in response to the fact that certain Carbon molecules have a price premium due to comparatively high demand. See: transportation fuels.

Nuclear heat also has the opportunity to stratify itself among different products. There is a range of quality inasmuch as you can produce different temperatures with a nuclear reactor and making 1 Btu at a lower temperature is easier for a host of reasons, these are mostly materials/technological, although there is some neutron economy difference if we assume that we're speaking of thermal reactors only.